This post covers the award winning novels from genres such as science fiction and mystery as well as the prestigious French literary prize, The Priz Goncourt.

The Hugo Award:

The Wanderer, Fritz Leiber, Tom Doherty Associates, 1964, 311 pp

The Wanderer earned Fritz Leiber his second Hugo Award. He won the first time in 1958 with The Big Time. I liked this one a good deal better.

An eclipse of the moon turns out to include the arrival of a rogue planet, four times the diameter of the moon and giving off a bloody and golden light. Humans name it The Wanderer. Once the planet consumes the moon, tidal surges and massive earthquakes make Earth a terror.

In addition to the apocalyptic horror of it all, I thought Leiber did a great job of showing the effects on various people around our planet as tides roll into cities and submerge the streets, as ships at sea try to navigate, as a group of flying saucer buffs come up against the space program, and as an astronaut on the moon is captured by the alien planet.

It took me a while to get used to all the characters and the shifts between their stories, but overall I enjoyed the book as a wild tale. I am discovering that it pays off to read older sci fi. I always think about how it influenced the sci fi of today. The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu, Anathem by Neal Stephenson, Octavia Butler's work, The Broken Earth Trilogy by N K Jemisin. I bet they all read this one when they were growing up.

The Edgar Award:

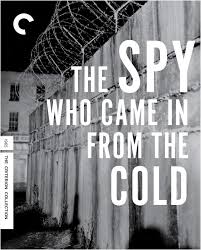

This was the #1 bestseller in 1964. The Edgar Award is for mysteries and sometimes thrillers. The movie starring Richard Burton came out in 1965 and has since been included in The Criterion Collection, as seen at the top of this page. My review of the book is here. It is sobering to post this today, just one day after the great John le Carre passed away.

The Nebula Award:

This award was given for the first time in 1965. I read the book for a reading group in 2018. My review is here. I have not read any of the sequels but I might see the movie version coming out in 2021. The book went on to tie for the Hugo Award in 1966.

The Prix Goncourt:

The Prix Goncourt is known as the premier French literary award, probably comparable to the Pulitzer Prize in the US. It has been awarding French novelists since 1867! I decided to add it to My Big Fat Reading Project whenever I can find an English translation of the winner for the year, which one usually can these days but not so much in earlier years. I found a library copy.

The Bond is an autobiographical novel about a man's rather tortured but undeniably close relationship with his mother. Borel includes a vast amount of detail; in fact one reference I found on Britannica.com described the writing style as Proustian or Joycean. For a while I felt I might not made it through such dense and introspective prose but finally I just gave myself over to it.

The son in the story was perhaps overly attached to his mother. You find out why as you read. Borel had kept a diary since the age of 14 and drew from it to write the book.

He portrays France from the post WWI years through WWII and the German occupation, his life in Paris as a child and adult through to the death of his mother. Thus he gives a 20th century personal history of French life during years when France was quite different than it is now. I found this fascinating.

I got plenty of insight into what it takes to write about one's own life. Since I am attempting to do that, it was useful. Having read most of Simone de Beauvior's memoirs, which cover the same time period, I could compare the two. Borel studied at the Sorbonne, as did she. In fact Beauvoir won this prize herself for The Mandarins in 1954, a book which I have read.